You’ve probably heard the worries about the viruses and other little nasties that are likely to emerge, still alive and kicking, from the permafrost as global warming continues to get worse. You might not know, though, that there are other things hanging out, frozen solid but waiting to re-join the world one day when things get just a little bit warmer.

For instance, the rotifers.

Image Credit: iStock

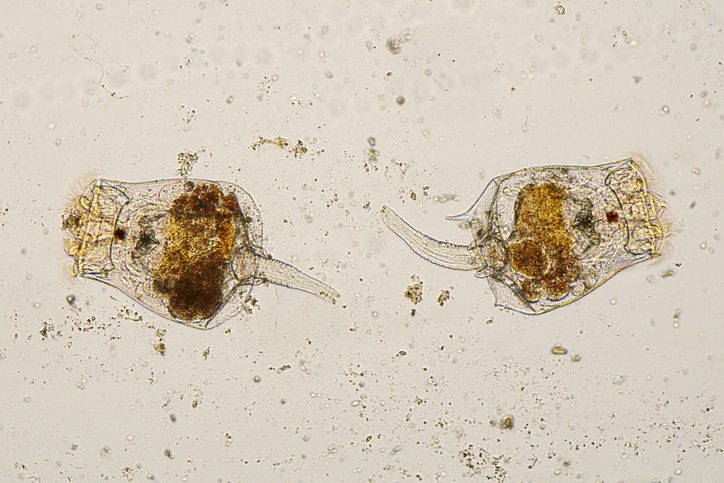

Rotifers are microscopic, freshwater-dwelling multicellular organisms that are known to withstand freezing, boiling, desiccation, and even radiation – and they can also survive for millions of years without having sex.

Even knowing all of that, researchers have been surprised by a recent study that unearthed living rotifers in 24,000-year-old Siberian permafrost.

The same researches previously found a 40,000-year-old viable roundworm in the permafrost, as well as ancient moss, seeds, viruses, and bacteria – the latter two of which have sparked legitimate concern over whether they could potentially cause harm to humans and other species when they thaw out.

Image Credit: iStock

Rotifers, though, generally hang out at the bottom of the food chain and aren’t much concern for the health of humans or higher order mammals.

The research being conducted by the Soil Cryology Lab in Pushchino, Russia, has been ongoing for more than a decade. They estimate the ages of the organisms they find by carbon dating the surrounding soil samples, resulting in a “frozen zoo” of sorts.

Now, the researchers are interested in learning how the organisms not only survived the freezing process, but are looking for insight as to how they continued to live for so long under the ice.

What they’ve found so far is that not all of the clones survived and the ones that did were only slightly more freeze-tolerant than their closest genetic relative. The key seems to be a relatively slow freezing process, one that takes place over 45 minutes or so, and they’re able to survive ice crystals forming inside their cells – something that is usually catastrophic for living organisms.

Image Credit: iStock

They’re hoping this might be able to help move the field of cryopreservation forward, if they can understand it. The process is obviously harder the larger the organism in question, but rotifers are the most complicated cryopreserved species to date – they have organs like a brain and a gut – so it’s exciting nonetheless.